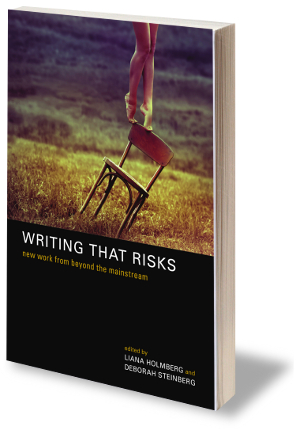

Michelle S. Lee talks with Red Bridge Press editor Seth Amos about pinhole camera poems, anti-influences, and how the Internet is helping poetry thrive. Her poem “The Myth of the Mother and Child” appears in Writing That Risks, the new anthology now available from Red Bridge Press.

Michelle S. Lee: I have been writing stories in one form or another since I was a kid. I still have the small, stapled pages that tell the tale of a lemon meringue pie who just wanted to be eaten. When I was a little older, I sent a query letter to a publisher of Beatrix Potter books, believing I also had, in a manuscript pecked out on a typewriter, captured the lively happenstances of mannerly and quite moral field animals.

into this tight space and sees an entire world that will only last a second.

SA: Can you talk about the first poem you wrote that made you think Yes, this is a poem?

MSL: Hmm. In thinking back over years of writing poems, I honestly have to say that only over the last year have I begun to reach a level of fullness, of understanding, of experience that makes me think, “Boom,” when I get to the last word. I sit back and look at the form, the imagery–and I realize that the poem is no longer mine; I read the words aloud over and over and hear not my voice, but the voice of a speaker instead, expressing ideas that come from me and outside me, beyond me. Recently, I’ve worked with editors who have asked me to change a word here and there, to break a line differently, to rethink a sound. I don’t take long to consider the revision: the poem belongs more to the reader than to me, and a re-vision is part of the process. I appreciate the growth. I have also had recent readers of my work attempt to force me into “claiming” certain lines as confessions; I laugh because by the time they read the piece, I don’t see myself in it at all.

SA: How do you feel teaching influences your own work?

MSL: This question makes me a bit embarrassed. I write the most when I teach, because–and I hesitate to be so honest and horribly egotistical here–I feel like I need to equalize the poetic karma in the world. I usually begin my course discussing bad poetry: everything from clichés to sugary confessionals. Then we spend weeks reading across styles and voices: everyone from Nikki Giovanni and Robert Frost to Marge Piercy and Brian Doyle. But somehow along the way, I still get odes bemoaning breakups by name and sonnets about love being as rich as diamonds, and I find myself running for pen and paper (yes, I am that old school) to stir up something with words.

But on a more positive note, the constant conversation about writing keeps me inspired. The talk about sounds and form and imagery and lyric, the discussion about line break and experiment, reminds me that I am a writer first.

SA: I want to talk about influences, but I don’t want to ask you what writers influenced you, so I will ask you for an anti-inspiration of sorts. Is there a widely adored writer whom you cannot stand nor fathom their popularity? How has your dislike of this writer influenced your writing?

MSL: There isn’t one person. It’s more like a type. The Quintessential Literary Elite. The QLE gets published and revered because of the workshop or school he or she attended; gets published for being “experimental,” when really his/her work resembles chicken feed scattered on a page. The QLE is prolific, but when you read his/her collections of poems or stories back to back, you realize he/she has simply recast the same poem or story again and again. The QLE believes in abstraction, believes there is no sexiness in the ordinary, the personal. The clear. The straight-forward.

I suppose this type of writer doesn’t influence my writing, but rather my actions as a professor, as a writer in my community. I organize events at school that make poetry and writing accessible. I imagine projects with colleagues that bring poetry into new circles and to new audiences. I try to champion language and writing that reveals the poetic in the real.

to blow moments wide open.

SA: What is your analysis of 21st century poetry in its present state? What do you think the poem will accomplish in the future?

MSL: Because of the internet, poetry has become more available. Places to read poetry, places to submit poetry. More creative folks have the opportunity to reimagine the literary journal and its space. There are so many more small, beautiful presses. Poetry can exist across form and spread into new genres. Poets can have their work published as letterpress cards, as audio recordings, as moveable type, as images unfolding on screen.

Poetry still seems like a genre for the elite, but with these new forums, shapes, sizes, and editorial choices, it could claim a prime spot in this world where emotions are “insta” and tweeted and texted and facebooked. Poems are tidy in stature, yet have the capacity to blow moments wide open.

Michelle S. Lee experiments with multi-genre texts, as well as the novella form and has been published in a variety of literary spaces and genres, including the introduction to a Simon & Schuster Enriched classic, a podcast/article for the Poetry Foundation, and pieces in Text and Performance Quarterly and Northwind Magazine. She is an associate professor at Daytona State College where she teaches composition and creative writing. Find her at doctormichellelee.blogspot.com.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed