Poet LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs sits at her computer to talk with editor Seth Amos, at his computer, about poetic form and the trials of hair maintenance.

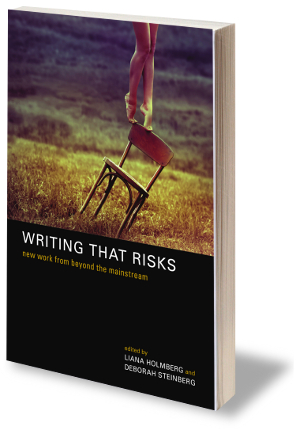

LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs is a vocalist, writer, and sound artist who publishes and performs extensively. She is one of twenty-nine authors from around the world whose work appears in the new anthology Writing That Risks: New Work from Beyond the Mainstream from Red Bridge Press.

Seth Amos: Your poem in the anthology, “bacche kā pōtRā,” is a golden shovel, a form created by Terrance Hayes when he used a line from Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem “We Real Cool.” Why did you decide to use this form, and how do you approach form for other poems?

LaTasha Diggs: I was invited to submit to another anthology that was focusing on the form. Before that time, I knew nothing about the golden shovel. But upon reading Terrance's poem and understanding how it was constructed, it made me curious. I ended up writing about eight within a week. Most loosely stuck to the formula. I don’t consider myself a formalist. When I decide to play with one, often it has to do with examining a language and finding ways in which my interests in using multiple languages can be juxtaposed against a form. Basically, I give myself a bigger headache.

Seth Amos: Your poem in the anthology, “bacche kā pōtRā,” is a golden shovel, a form created by Terrance Hayes when he used a line from Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem “We Real Cool.” Why did you decide to use this form, and how do you approach form for other poems?

LaTasha Diggs: I was invited to submit to another anthology that was focusing on the form. Before that time, I knew nothing about the golden shovel. But upon reading Terrance's poem and understanding how it was constructed, it made me curious. I ended up writing about eight within a week. Most loosely stuck to the formula. I don’t consider myself a formalist. When I decide to play with one, often it has to do with examining a language and finding ways in which my interests in using multiple languages can be juxtaposed against a form. Basically, I give myself a bigger headache.

"to groom was spiritual once"

SA: There’s a versatile movement in “bacche kā pōtRā” brought on by the repetition of the word “wave”. Where do you feel this takes the poem?

LD: Waves of emotions. Hair blowing in the wind. Waving goodbye. I would hope that it takes you to each definition as you learn a little something about the trauma of some popular hairstyles worn by women of African ancestry.

SA: Can you talk about the line “to groom was spiritual once”?

LD: In many different African cultures, besides the general maintenance of hair, the styling of hair indicated one’s status, ethnicity, religion, social rank, etc., and thick hair was most desirable. Growing up, there were always one or two women that knew how to cornrow hair. They would teach their daughters or a next door neighbor and it just kept being passed on from generation to generation.

SA: Fred Moten’s poem “eleven maroons” provides the line that you include in your golden shovel. How does your poem relate to his?

LD: It doesn’t.

SA: [laughs] Was the poem written around the Moten line or was the line a secondary thought to your inspiration for the poem?

LD: I would say both. When reading Moten’s line, I kept thinking about Dr. Seuss original TV adaptation of The Lorax. When digging into the many phrase books I have at home, I came across the term “bacche kā pōtRā”. In Hindi/Urdu this means “nappy,” but of course the phrase book does not go into detail as to how “nappy” is being used. So not knowing gave me a lot of ideas to play around with. Also, truffula trees look like “the kitchen” of a Black woman’s natural hair line. So the poem, while it has this little story going on, it is translating and mistranslating this word. It also reflects back to the tradition of hair grooming--and the irony that one of the largest suppliers of human hair extensions is South East Asia.

LD: Waves of emotions. Hair blowing in the wind. Waving goodbye. I would hope that it takes you to each definition as you learn a little something about the trauma of some popular hairstyles worn by women of African ancestry.

SA: Can you talk about the line “to groom was spiritual once”?

LD: In many different African cultures, besides the general maintenance of hair, the styling of hair indicated one’s status, ethnicity, religion, social rank, etc., and thick hair was most desirable. Growing up, there were always one or two women that knew how to cornrow hair. They would teach their daughters or a next door neighbor and it just kept being passed on from generation to generation.

SA: Fred Moten’s poem “eleven maroons” provides the line that you include in your golden shovel. How does your poem relate to his?

LD: It doesn’t.

SA: [laughs] Was the poem written around the Moten line or was the line a secondary thought to your inspiration for the poem?

LD: I would say both. When reading Moten’s line, I kept thinking about Dr. Seuss original TV adaptation of The Lorax. When digging into the many phrase books I have at home, I came across the term “bacche kā pōtRā”. In Hindi/Urdu this means “nappy,” but of course the phrase book does not go into detail as to how “nappy” is being used. So not knowing gave me a lot of ideas to play around with. Also, truffula trees look like “the kitchen” of a Black woman’s natural hair line. So the poem, while it has this little story going on, it is translating and mistranslating this word. It also reflects back to the tradition of hair grooming--and the irony that one of the largest suppliers of human hair extensions is South East Asia.

Poet and vocalist LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs has been published in Ploughshares, Jubilat, Fence, LA Review, and Black Renaissance Noir, among others. Her performance work has been featured at The Kitchen, Exit Art, Recess Activities Inc, The Whitney, and MoMa. As a curator and artistic director, she has staged events at El Museo del Barrio, Lincoln Center, Symphony Space, Dixon Place, and BAM Café. She is the recipient of several awards, including Cave Canem, New York Foundation for the Arts, Jerome Foundation, Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and The Laundromat Project. Along with Greg Tate, she edits yoYO/SO4 Magazine. Her poetry collection TwERK was recently published by Belladonna*. She is a native of Harlem. More at latashadiggs.tumblr.com.

Find LaTasha's poem and twenty-nine other world-expanding works in Writing That Risks.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed