Red Bridge Press author David Dickerson talks with editor Deborah Steinberg about experimental fiction and his love of comics and puzzles.

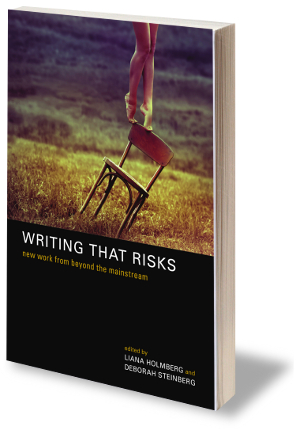

David Ellis Dickerson’s story “Display Wings” opens the forthcoming Red Bridge Press anthology Writing That Risks. It’s a whimsical and poignant piece about a museum docent desperately trying to reorganize the museum’s collections according to a new system of categorization while a rebel army might or might not be on its way to burn the place down. Dickerson is a regular contributor to This American Life on NPR, and has published a memoir, multiple works of short fiction, and essays in places as diverse as The Atlantic Monthly and Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror. He teaches composition, creative writing, and African-American literature, and also draws comics.

Deborah Steinberg: Your memoir, House of Cards, is about working as a greeting card writer for Hallmark as a young MFA graduate. Since then, you’ve been a frequent contributor to NPR’s This American Life and you draw comics. How do these more mainstream pursuits relate to your interest in experimental fiction?

David Dickerson: The uniting element is surprisingly simple: humor. I got into greeting cards because I liked drawing cartoons and writing light verse. I got into telling funny stories on the radio in the same way. And my favorite experimental fiction authors are the ones who are funny, from the classic purveyors like Italo Calvino and Donald Barthelme to modern geniuses like Aimee Bender and Karen Russell. To my mind, a well-executed experimental fiction is a sort of joke or puzzle that exists to satirize readerly conventions.

The other way the mainstream pursuits relate to experimental fiction is a little sadder: they fund it. Experimental fiction rarely hits the bestseller lists. Those of us who love it have to pursue it as a sideline, and I’m very fortunate that most of my sidelines also involve writing.

Deborah Steinberg: Your memoir, House of Cards, is about working as a greeting card writer for Hallmark as a young MFA graduate. Since then, you’ve been a frequent contributor to NPR’s This American Life and you draw comics. How do these more mainstream pursuits relate to your interest in experimental fiction?

David Dickerson: The uniting element is surprisingly simple: humor. I got into greeting cards because I liked drawing cartoons and writing light verse. I got into telling funny stories on the radio in the same way. And my favorite experimental fiction authors are the ones who are funny, from the classic purveyors like Italo Calvino and Donald Barthelme to modern geniuses like Aimee Bender and Karen Russell. To my mind, a well-executed experimental fiction is a sort of joke or puzzle that exists to satirize readerly conventions.

The other way the mainstream pursuits relate to experimental fiction is a little sadder: they fund it. Experimental fiction rarely hits the bestseller lists. Those of us who love it have to pursue it as a sideline, and I’m very fortunate that most of my sidelines also involve writing.

“The Distance of the Moon” quite literally saved my creative sanity

DS: What are some of your favorite works of experimental fiction? How did you first get interested in experimental fiction?

DD: When I entered my MFA program in fiction in the 1990s, I could tell right away I was in a bad spot. The realistic slice-of-life stories so many people traded in were not especially interesting to me, and they were like pushing string to write. I wondered if something was wrong with me. But then a stray reference to Italo Calvino in Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist led me to Cosmicomics, and the very first story in that collection, “The Distance of the Moon,” quite literally saved my creative sanity. For years, Calvino was my model of a short story writer. Then, several years later, I read Barthleme’s “The Dead Father,” and that blew my mind so much, and it was so unlike any novel I’d ever read, that it seemed like I’d emerged from a cave into a world with more colors than I’d ever been allowed to imagine existed. I’ve reread that book and Calvino’s Invisible Cities at least a dozen times. I will forever be grateful to them both; they made me think I could do this.

DS: What was the genesis for your story “Display Wings”?

DD: I’m fascinated by museums, and the story actually started with a long cultural-studies essay on museums—in a book so academic that its title contained two virgules—that talked about how Darwinism changed the organization of museums, and also mentioned that during the Chartist Rebellion, the British Museum really did have guards and boiling oil on the roof, just in case the labor rioters came to destroy All Of Culture. So I wanted to explore both of those very strange pressures, as well as the strangeness of museums themselves, with help from a character coming from (consciously) outside the culture.

DS: In addition to writing books and telling stories, you draw humorous comics. Can you tell us a bit about how the different forms in which you work—but particularly comics as opposed to prose—serve different aspects of your creative expression?

DD: I’ve always doodled, and when I started writing silly poems and doing stand-up, it was clear that I was also coming up with joke ideas that didn’t work well either as poems or as gags on stage; I needed the visual. For example, I have a cartoon titled, “Graph of Titanic Sinkings, By Year” and it just shows a graph from 1800 to 2050, with a single spike—1 Titanic sinking!—at 1912. It’s a funnier image than it is a sentence, and the beautiful thing about a good cartoon is that it can take a little wisp of a joke like that and express it in exactly the tiny amount of time it deserves. Meanwhile, in talking about it here, I’ve already gone way too long.

DD: When I entered my MFA program in fiction in the 1990s, I could tell right away I was in a bad spot. The realistic slice-of-life stories so many people traded in were not especially interesting to me, and they were like pushing string to write. I wondered if something was wrong with me. But then a stray reference to Italo Calvino in Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist led me to Cosmicomics, and the very first story in that collection, “The Distance of the Moon,” quite literally saved my creative sanity. For years, Calvino was my model of a short story writer. Then, several years later, I read Barthleme’s “The Dead Father,” and that blew my mind so much, and it was so unlike any novel I’d ever read, that it seemed like I’d emerged from a cave into a world with more colors than I’d ever been allowed to imagine existed. I’ve reread that book and Calvino’s Invisible Cities at least a dozen times. I will forever be grateful to them both; they made me think I could do this.

DS: What was the genesis for your story “Display Wings”?

DD: I’m fascinated by museums, and the story actually started with a long cultural-studies essay on museums—in a book so academic that its title contained two virgules—that talked about how Darwinism changed the organization of museums, and also mentioned that during the Chartist Rebellion, the British Museum really did have guards and boiling oil on the roof, just in case the labor rioters came to destroy All Of Culture. So I wanted to explore both of those very strange pressures, as well as the strangeness of museums themselves, with help from a character coming from (consciously) outside the culture.

DS: In addition to writing books and telling stories, you draw humorous comics. Can you tell us a bit about how the different forms in which you work—but particularly comics as opposed to prose—serve different aspects of your creative expression?

DD: I’ve always doodled, and when I started writing silly poems and doing stand-up, it was clear that I was also coming up with joke ideas that didn’t work well either as poems or as gags on stage; I needed the visual. For example, I have a cartoon titled, “Graph of Titanic Sinkings, By Year” and it just shows a graph from 1800 to 2050, with a single spike—1 Titanic sinking!—at 1912. It’s a funnier image than it is a sentence, and the beautiful thing about a good cartoon is that it can take a little wisp of a joke like that and express it in exactly the tiny amount of time it deserves. Meanwhile, in talking about it here, I’ve already gone way too long.

how amazing it is that words—just words on a page!—can do the astonishing things they do to our insides

DD: I think my interest in cartooning is, in fact, related to my love of experimental fiction, because when I’m switching away from, say, poetry to a cartoon, I’m doing it because I’ve noticed that I have a job to do and I need to reject some of my usual tools. One of the things we sometimes forget about writing is that it’s a pretty terrible way to describe anything. Words excel at the philosophical and the psychological: In a story or an essay, we know how a particular dinner table looks—the quick emotional/cultural sweep of its impact—according to a single narrator’s perspective, but to get what it actually looks like—how long the legs are, how fast those legs taper, is the tablecloth kind of shiny and does it drape over your thighs when you pull up a chair—requires a hideous chain of sentences that a photograph can handle in seconds. TV and movies are much better at registering a character’s complicated expression than fiction could ever be. But nothing has ever matched writing for conveying in-depth thoughts or emotions. And I think, in the end, that’s what draws me to experimental fiction: it’s fiction that foregrounds its artificiality, its word-dependence, and I’m inclined to say that those of us who love experimental fiction are the sorts of people who enjoy being reminded at how amazing it is that words—just words on a page!—can do the astonishing things they do to our insides. I hope we never stop being amazed.

DS: Anything else you’d like to share with the Red Bridge community?

DD: Well, another feature of my writing that hasn’t come up is that I’m a professional crossword puzzle constructor, and there’s a pretty strong connection between the two practices: writing experimental fiction is presenting a puzzle to a reader, along with clues that tell the reader how to take it in.

DS: Anything else you’d like to share with the Red Bridge community?

DD: Well, another feature of my writing that hasn’t come up is that I’m a professional crossword puzzle constructor, and there’s a pretty strong connection between the two practices: writing experimental fiction is presenting a puzzle to a reader, along with clues that tell the reader how to take it in.

Learn more about David Dickerson.

Be the first to get Writing That Risks! Join our mailing list.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed