Red Bridge authors share what takes them to the edge in their writing -- and why they go there. What are the biggest risks they've taken? How did they turn out?

In the second installment of this two part series, we hear from Libby Hart, Joanne M. Clarkson, Sharif Shakhshir, and Christina Olson.

In the second installment of this two part series, we hear from Libby Hart, Joanne M. Clarkson, Sharif Shakhshir, and Christina Olson.

Libby Hart: The biggest risk is something I try to attempt again and again. It is to let go of the wheel when I begin to write a poem in order for the creative process to take over. It’s at this point that I fully accept writing is often communion with the unknown.

I just keep on heading north, following the Mississippi of the mind.

Generally, I know what I want to focus on in a poem, but what shape it takes from there is an unexpected journey. It’s a road of twists, of bends. There is the odd roller-coaster or two. Up. Down. Slam on the brakes! Reverse. Turn right. Go a little further then do a U-turn. Again and again there are dead-end streets. But somewhere toward the end of a first draft I will sit with the words and begin to interpret a map that was not present beforehand. Someone turns on the headlights and I can see a stretch of road before me. Once I get to this stage I take hold of the wheel again and get on with the act of driving this little vehicle. Sometimes I have to wait for a time at stop signs or red lights. Sometimes I just keep on heading north, following the Mississippi of the mind. Softly, softly there is a favorite song playing on the radio. I hum along. I wind down the windows. I’m reminded of how much I love the wind.

Joanne M. Clarkson: A few years ago I went through a crisis of soul when I felt I was not ‘worthy’ to write poetry because I was not sure my life had mattered enough. I was not sure I truly had enough to say. I was also wrestling with the meaning of ‘courage’ and what constituted a hero. I read many biographies of people of service. As with most types of depression, I got over it when I began looking outward. And when I began to tell the truth.

I started by stealing. I wrote little bits about the tribulations of neighbors, friends and people in the newspaper. I began to understand how people faced difficulty not with the mind but through the heart. Gradually I came around to writing about my own heart. And from my own heart. And I came back to poetry.

Now I feel comfortable writing about my failings and flaws. Not that I write confessional verse at all. And my flaws can be couched in trees or old men or the way cloth drapes saints in museums. I guess I equate risk with empathy. And willingness to say how anything REALLY feels.

“Best Pony” is a game that asks you not to play.

Sharif Shakhshir: I wrote a long poem with only questions, and those questions mostly involved My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic. This runs counter intuitive to the expectations of poetry. It’s supposed to be short, provide answers, and be “high art.” “Best Pony” is a game that asks you not to play. It’s a risk, but the risk is part of the game. The deserving follow the rabbit into wonderland… Or should I say they follow the ponies into wonderland? Looking past the pop-art (the pop-art is a weapon and there to disarm you) and the humor (a laughable lure) you find that things get serious, real, and maybe close to home. It does things a poem like this shouldn’t.

However, when you dare a publisher not to play a game, they will usually take you up on that. Yet, when read aloud to a captive audience who cannot help but play the game, “Best Pony” leaves an impact. After reading it at the LA Times Festival of Books a woman told me, “[Best Pony] shouldn’t have been good, but it’s amazing and sad.” This poem’s never been published, but to have that effect on someone makes me feel the risk was worth it.

Christina Olson: The biggest risk I’ve taken in my writing is writing about whatever I please. In the last few years, I stopped worrying that a lit mag or publisher wouldn’t like a subject and just wrote about things (or embarked on projects) that I was interested in--and it’s been such fun. (Not that I was always thinking, Oh, I better write a poem about Bigfoot living in Texas; that will sell! but I think writers tend to worry I haven’t seen people do something like this before: I’m sure everybody will think it’s too weird.) Instead, I’ve been working on a chapbook-length series of poems loosely based on 1990s episodes of Law & Order, or writing an eight-part poem about the Coney hot dog, or making found poems out of old emails. And it turns out those have been well-received. People like talking about television and hot dogs. Meanwhile, I’m happier for writing about them.

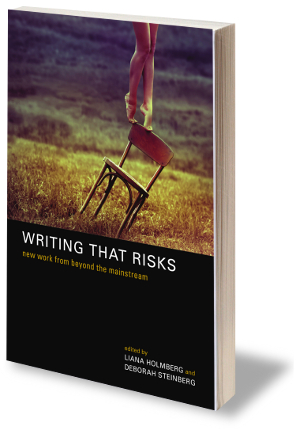

Find work from these authors and more in Writing That Risks: New Work from Beyond the Mainstream.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed