Red Bridge authors share what takes them to the edge in their writing -- and why they go there. What are the biggest risks they've taken? How did they turn out?

In the first installment of this two part series, we hear from John Newman, Olga Zilberbourg, Edmund Zagorin, and Michelle S. Lee.

In the first installment of this two part series, we hear from John Newman, Olga Zilberbourg, Edmund Zagorin, and Michelle S. Lee.

John Newman: For me writing is the risk, and if you’re writing and your heart isn’t beating faster, then what you’re actually doing is typing. Everything I write begins with a tiny explosion in my brain that coughs up an image, a character, a first line. And I can see it, and I can feel it and hear and smell it. And I close my eyes for just a moment and the whole thing happens right there inside me; I see it all from beginning to end and it’s so fucking perfect. And then...well, I have to somehow put down that story in words. I have to reach inside and pull it out intact, without breaking it, without my great clumsy paws warping it beyond recognition. And I know it’s impossible.

Writers are junkies

The very process of writing is one that is (in my case anyway), almost certainly doomed to fall just that that tiny bit short of truly capturing the idea that fueled the whole thing to begin with. But maybe it’s that anarchistic fatalism that spurs us on and makes the next piece inevitable. Writers are junkies, and they’re junkies who can’t be cured and wouldn’t want to be even if they could.

Olga Zilberbourg: I like a formal challenge. For example, writing in a first person collective we voice that doesn’t resolve in a single first person speaker I but transitions into the third person they. For example, “We went to the store to buy groceries. Anna wanted whole milk but Ben wanted 2%. We stood in the middle of the aisle and glared at each other.” It’s a fun way of writing about a couple or about a small group of friends who think they’re on the same page but aren’t quite. The danger, of course, is that a story like this might seem incomprehensible. Readers will keep asking me, “But who’s really speaking?”

Edmund Zagorin: Early stories I published under a pen name because I was nervous writing about sex. On the one hand, sex is just another banal aspect of planetary life. On the other hand, it is maybe the number one thing that makes people’s blood boil. I love to write moving in between places, which is how the Aztec story happened. On an airplane , I saw two people sitting in adjacent seats, shifting their weight around uncomfortably, and I thought: four and five hundred years ago, they might have been at each other’s throats. Now they fight over an airplane armrest instead of spilling blood and treasure. Old enmities smolder along tenaciously, but do you ever even the score? Such a question can be a reason to write stories.

Before writing and submitting certain poems and stories,

I questioned their public life.

Michelle S. Lee: Over the last year, I have become more “real” in my writing. I have delved into the gray areas, issues of ordinary life: marriage, children, fantasies, desires.

The reason going “real” is, and has been, risky: my readers (friends, colleagues, students, readers) believe that the speaker of a poem, or the main character in a short story, is me. Of course, the work comes from my psyche. But it may not be who I am. It is comprised of ideas, observations, pieces of glass held up to a world I see.

Before writing and submitting certain poems and stories, I questioned their public life. I wondered what people would imagine, wondered how they would fill in the blanks, wondered if I would be viewed differently. What if my family was viewed differently? Yet when I looked at these works, I saw a level of depth I had never reached before. So out they went.

And I have gotten the comment: Is this you? Did this happen? And I said and will say: it’s poetry, it’s fiction. You cannot assume the speaker or narrator is more than anything than on the page.

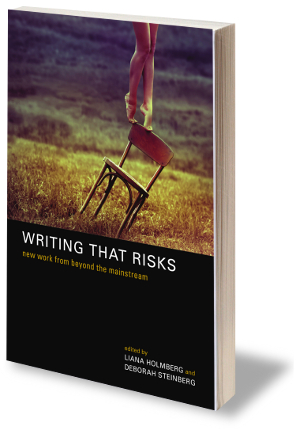

Find work from these exciting authors and more in Writing That Risks: New Work from Beyond the Mainstream.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed